The rise of the AfD: why Germany’s hard right keeps gaining ground

Why are the Alternative for Germany so popular — and where will they go next?

A recurring theme of this newsletter is the rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD). This article sets out why the party has grown so quickly, why efforts to contain it have backfired, and what its continued rise means for Germany’s political system — regardless of whether one views the AfD as a symptom, a threat, or a corrective.

The origins of the AfD

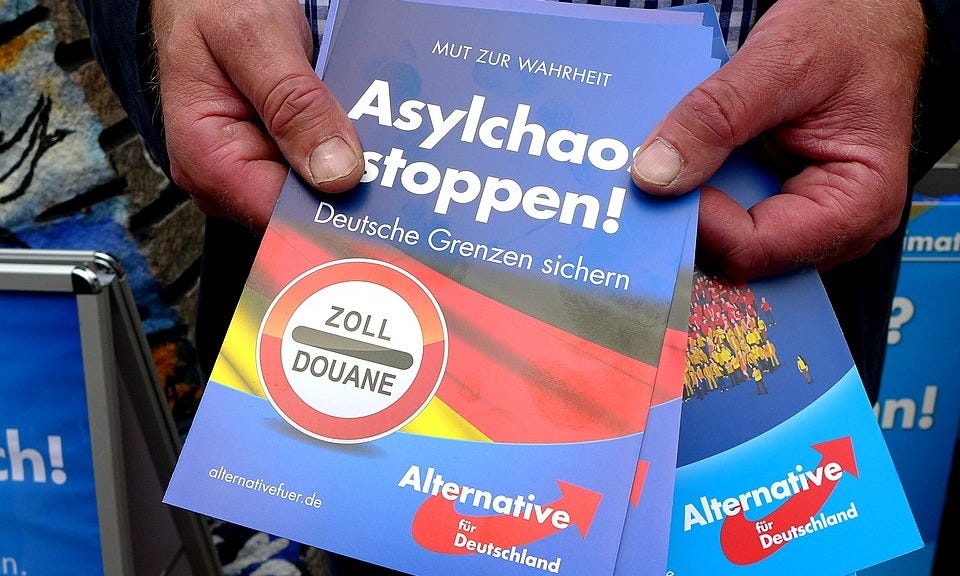

Founded in 2013 as an anti-Euro party, the Alternative for Germany have become best known internationally for their rejection of mass migration, particularly when it comes from the Muslim world.

More than that though, they oppose many, if not all, the major developments that German society has undergone over the past two to three decades. They argue that Germany’s green energy policies - and the nuclear shutdown - are driving the country into poverty; they want to re-establish normal relations with Russia; and they remain highly sceptical of both the single currency and the EU as a whole, which they see as unaccountable institutions that have hollowed out national democracies.

What attracts people to the AfD?

For their supporters, the AfD offer hope of a return to Germany’s post-war heyday when the state played a relatively small role in people’s lives. They see the AfD as the last chance of saving the Federal Republic from a linksgrüne Zeitgeist that is driving business and skilled labour abroad, has no respect for the achievements of the country’s past, and favours ideology in foreign policy over sober pursuit of the national interest.

Angry at what they see as social engineering of how they talk, what they are allowed to say, and even how they eat, voters are turning to the AfD in droves in the belief that they represent a return to an era when politicians kept their noses out of the public’s private affairs.

From this perspective, it makes sense that the AfD have scored their biggest successes in former East Germany. Five decades of living in a planned economy where the citizens had to toe the party line left voters there allergic to a political class who are better at giving lofty sermons than they are at doing the basics of running an economy.

The way that opponents have dealt with the AfD only appears to confirm the impression that the political establishment is a self-serving elite: when a movement emerges that offers a genuine alternative to the status quo, the establishment has opted for repression rather than engagement.

Domestic intelligence agencies, which take orders from state and federal interior ministries, snoop on AfD members’ communications and even have a network of informants in the party. In legislatures, the other parties band together to stop the AfD from taking on even symbolic roles - to the extent that they are excluded from playing in the Bundestag football team.

What people fear about the AfD

Opponents would recognise little of the above description. For them, it is the AfD who are deliberately trying to undermine the respect for human rights that Germany’s post-war constitution is based upon and replace it with an ethno-national mono-culture.

To achieve this goal, the AfD are using classic populist methods of demonising hard-working political opponents and cynically opposing every new law without putting forward realistic alternatives. In truth, their leadership are reactionary, anti-American nationalists, who want to ignore the horrific lessons of German 20th century history and set up a European state system that is once again based on large countries dominating smaller neighbours.

Furthermore, they are engaged in a dangerous game of revisionist history whereby they try to play down the horrors of the Nazi era, with some senior figures in the party even trying to use Nazi slogans to either appeal to a neo-Nazi fanbase or normalise rhetoric that was long taboo.

Meanwhile, their opposition to Muslim migration is exactly the same sort of scapegoating that the Nazis carried out with the Jews. Feeding on German anxiety over a weakening economy, they have found an easy target for people’s anger. The AfD’s dangerous rhetoric has already led to a sharp rise in xenophobia, with chants that were once confined to the dingy bars of neo-Nazi hooligans are now becoming surprisingly popular among the country’s youth.

At the same time, the AfD is not a unified ideological project in the way fascist movements historically were. It is internally fragmented, often strategically incoherent, and lacks a single national leader capable of imposing discipline across the party.

State repression?

Germany has a unique constitution: borne out of the experience of the Nazis rise to power via democratic means, it explicitly allows for organs of state to intervene to prevent a new form of fascism from sabotaging democracy from within. For opponents of the AfD, that time has now arrived. Wehret den Anfängen, they warn, as they call for the intelligence services to watch the upstart party like a hawk, something that could pave the way for an outright ban by the Constitutional Court.

Even if they never end up being banned, accommodating them would be the height of foolishness, opponents say. Several senior AfD figures have suspected links to the Kremlin, meaning that giving them access to state secrets would be the height of irresponsibility.

Whatever perspective you take on this - and there is certainly truth to be found in both narratives - the AfD doesn’t appear to be going anywhere any time soon. At the 2025 election they came second, making them the first party to break the 80-year CDU/SPD duopoly of the post-War era.

Why containment has failed

Attempts to prevent their rise by ostracising them have failed. At the same time, the AfD are far away from winning absolute majorities, meaning that the remaining parties will be able to keep building coalitions against them, should they so choose. But, ever broader anti-AfD coalitions, from centre-right to far-left, pose their own problems for Germany’s democratic system.

Even without entering government, the AfD’s strength is already reshaping German politics: forcing ever-broader coalitions, paralysing decision-making, and encouraging other parties to adopt positions they once ruled out.

Where will things go from here? Some pollsters say that the AfD, polling at around 25 percent, have hit the upper limit of their potential. Other analysts point to the example of neighbouring countries like the Netherlands and Austria to suggest that it is only a matter of time before the hard-right party emerges as the outright winners at state and national elections.

To an extent, centrist politicians still control their own destiny. Attempts to drastically cut illegal immigration are already underway. Reversing the processes of de-industrialisation will require even bolder leadership, as it will require a delay to Germany’s self-defeating moratoriums on the use of fossil fuels.

On the other hand, this struggle between the ‘powers that be’ and the AfD has taken on its own momentum. When and if the AfD’s seemingly unstoppable rise starts to falter may have less to do with any single policy decision taken in Berlin and more to do with something much harder to put a finger upon: a imperceptible shift in the stories German society is telling itself.

If the AfD do emerge as the largest party in the German political landscape, all bets are off about what would happen next. With narratives around the party so apocalyptic in their proportions, political violence is already on the rise (with AfD politicians most often the victims). Whether the AfD are finally brought in from the cold, or their ostracization continues, the potential for unrest will only grow.

That’s a valid comment, perhaps if Merz actually moved on some of his promises - particularly regarding immigration - the AFD popularity may slow down…

History should tell us to at least engage even if we totally disagree….There is a saying…. “Keep your friends close, keep your enemies closer “