Why German spies wiretap the AfD

The hard-Right party are being watched by spooks. Is that fair?

Dear Reader,

In mid-January it seemed like a certainty. Newspaper reports suggested that all 16 state interior ministers were in agreement and that the federal interior minister, Horst Seehofer, had finally given his blessing.

For the first time in the history of the republic, the BfV domestic intelligence agency would declare an entire political party represented in the Bundestag a Verdachstfall - an organisation suspected of trying to subvert the constitution.

The Alternative for Germany - the official opposition with 92 MdBs - would be put under surveillance by the Verfassungsschutz (BfV). Such a move allows for spying on both MPs and ordinary party members; the spy service would be able to place informants inside the party.

The groundwork had been prepared over years. The party had initially been classified as a Prüffall (case of interest), then a powerful internal network known as Der Flügel (the Wing) was declared “extremist” last year.

However, the big announcement never came.

First, we heard that Mr Seehofer had got cold feet. Wary of a legal challenge, he got his in-house lawyers to pore over the 1,000-page indictment one more time.

In the meantime, the AfD took legal countermeasures, applying for an emergency injunction in a Cologne court. The court has since ordered the BfV to show the judges what evidence it had for its decision.

If, or when, the BfV boss announces in front of the media that the AfD are a Verdachtsfall, it will make international headlines.

What will gain less attention is the fact that a government agency is capable of directing its powerful tools against an opposition party. That’s a system that seems tailor-made for abuse.

It seems remarkable that this is considered normal. A politicized intelligence service poses a threat to free elections: that’s why spying on other political parties is prohibited in almost every other democracy across the world.

In the United Kingdom, for instance, the Wilson doctrine prohibits MI5 from eavesdropping on parliamentarians (although this admittedly hasn’t stopped them from breaching the convention on numerous occasions).

In a Superwahljahr, the AfD are unsurprisingly shouting about a political hit job. They claim, not without merit, that the very public label of “suspicious” by a state agency robs them of their constitutional right to impartial treatment.

It’s not just the AfD that has been selected for these shadowy state shakedowns. In the past the BfV have kept archives full of files on people with links to communist parties - even the Greens have had their phones tapped.

‘Resistant’ democracy

To understand why the BfV has such extensive powers, one needs to know when and why it was set up. It dates back to the year 1950, when the western Allies decided that Germany needed a muscular spy agency that could root out revanchist Nazis and nip any insurgency in the bud.

As such, it became the only executive arm of a constitutional system known as wehrhafte Demokratie (resistant democracy). The German constitution is rather unique, it doesn’t just have safe guards against violent revolution but also against revolution by legal means.

That’s an understandable arrangement for a country which was dealing with the immediate aftermath of the Nazi dictatorship. After all, Adolf Hitler didn’t come to power at the head of a violent mob. His attempt to do so in Munich in 1923 was a humiliating failure. Instead, he rose to power through electoral success and coalition-building. Then, when the time was right, he forced the Reichstag to vote itself into irrelevance via an infamous law known as the Ermächtigungsgesetz.

The whole German system is set up to hinder a repeat of that democratic coup. Government ministers must swear fealty to the constitution; even members of the public have a constitutional “right to resistance” as a last resort.

As the highest arbiter, the Verfassungsgericht - the Constitutional Court - sits in Karlsruhe. It has the job of banning an organisation if there is enough proof that it is a Verfassungsfeind - an enemy of the constitution.

While the Verfassungsgericht is the summit of an independent judiciary, the BfV spy service operates in a grey zone. It is not connected to the police or prosecution. As such, it does not need to obtain court orders for its investigations. It takes its instructions from the interior ministry, which is controlled by the governing party.

The heads of the BfV have themselves always been members of the major parties. Current BfV president Thomas Haldenwang is a from the Christian Democrats, as was his predecessor Hans-Georg Maaßen. Before that, the agency was run for twelve years by Social Democrat Heinz Fromm.

In theory at least, there is a check on abuses of power in the form of the Bundestag intelligence committee. But this committee is in reality weak: its decisions are made by majority vote - and the governing coalition always has a majority.

This all makes the BfV’s affairs highly delicate.

“The Verfassungsschutz, whenever it goes about its work, is always in danger of damaging democracy rather than protecting it,” writes Dr Dietrich Murswiek, one of the country’s foremost constitutional scholars, in an article on the limits of agency’s powers.

And, as Murswiek points out, a BfV that is open to political influence “can, by unfairly labelling a party as extremist, create a serious distortion of the democratic process, which could even be decisive in elections.”

Spying on the Left

For decades, the main targets of the BfV were on the left.

On a late January morning 49 years ago, chancellor Willy Brandt met the leaders of the west German states to sign off a new law. The Radikalenerlass (radicals decree) that they agreed upon is almost forgotten today, but it is as close as Germany came in the post-war period to McCarthyism. Just a few sentences long, it mandated that everyone hired by the state had to “guarantee that he would always be prepared to stand up for the constitution.”

The background to the decree was the bloody terror of the far-left Baader-Meinhof gang, who had been engaged in a deadly game of cat and mouse with Germany’s police.

While the fear of left-wing extremism was undoubtedly real, what followed was sweeping persecution of thousands of people who were exercising a basic right to freedom of assembly. Teachers, bureaucrats and postal workers were prevented from gaining employment - or sacked from their jobs - for association with the German Communist Party (DKP), a legal political organisation.

It was the job of the BfV to look into the backgrounds of people applying for state jobs.

By the time the decree was lifted in 1985 the BfV had checked up on over a million people, leading to an estimated 10,000 attempts to ban people from working in the public sector. Some 1,200 applicants were rejected for jobs on claims that they lacked dedication to the constitution. A further 260 people were fired from state jobs, their reputations in tatters.

The intent was clear: make the DKP a pariah by destroying the careers of its members.

On other occasions, the BfV’s activities seem to have been particularly targeted at elections.

The Green party found themselves under observation when they first broke onto the national political scene in the early 1980s. Information that the spy service gathered about them was even leaked to a CDU politician who tried to use it to damage their chances at the 1983 election.

The end of the Cold War didn’t mean that the Verfassungsschutz would leave the left in peace. The incorporation of the Neue Bundesländer into the Republik gave the spies had a whole host of potential Verfassungsfeinde to keep an eye upon.

For over twenty years after reunification, the agency kept files on politicians in the left-wing PDS, and its successor party, die Linke.

By 2012 more than a third of the Left party’s parliamentarians in the Bundestag remained under surveillance.

The justification given by the interior ministry was that there were organisations at the fringes of Die Linke still calling for a “dictatorship of the proletariat.” But there was no proof that these groups had any influence on the party hierarchy. The Linke election manifesto from 2009 reads like an old school Social Democratic text, with lots of reference to the constitutionally anchored right to human dignity. But this didn’t stop the BfV snooping on the leadership, including chairman Gregor Gysi and his faction deputy Bodo Ramelow.

For Petra Pau, a Linke veteran, “the BfV was clearly being instrumentalised for political gain.”

Ms Pau is, by the way, against the BfV observing the AfD. “I know from open sources and from daily interactions that there are racists in their ranks - I don’t need the BfV to tell me that” she told Deutsche Welle.

The informant paradox

Another core problem with the BfV is that its opaque activities actually hinder the work of the courts. There is only one recent example of an attempt to ban an extremist party. And that failed spectacularly - because of the BfV.

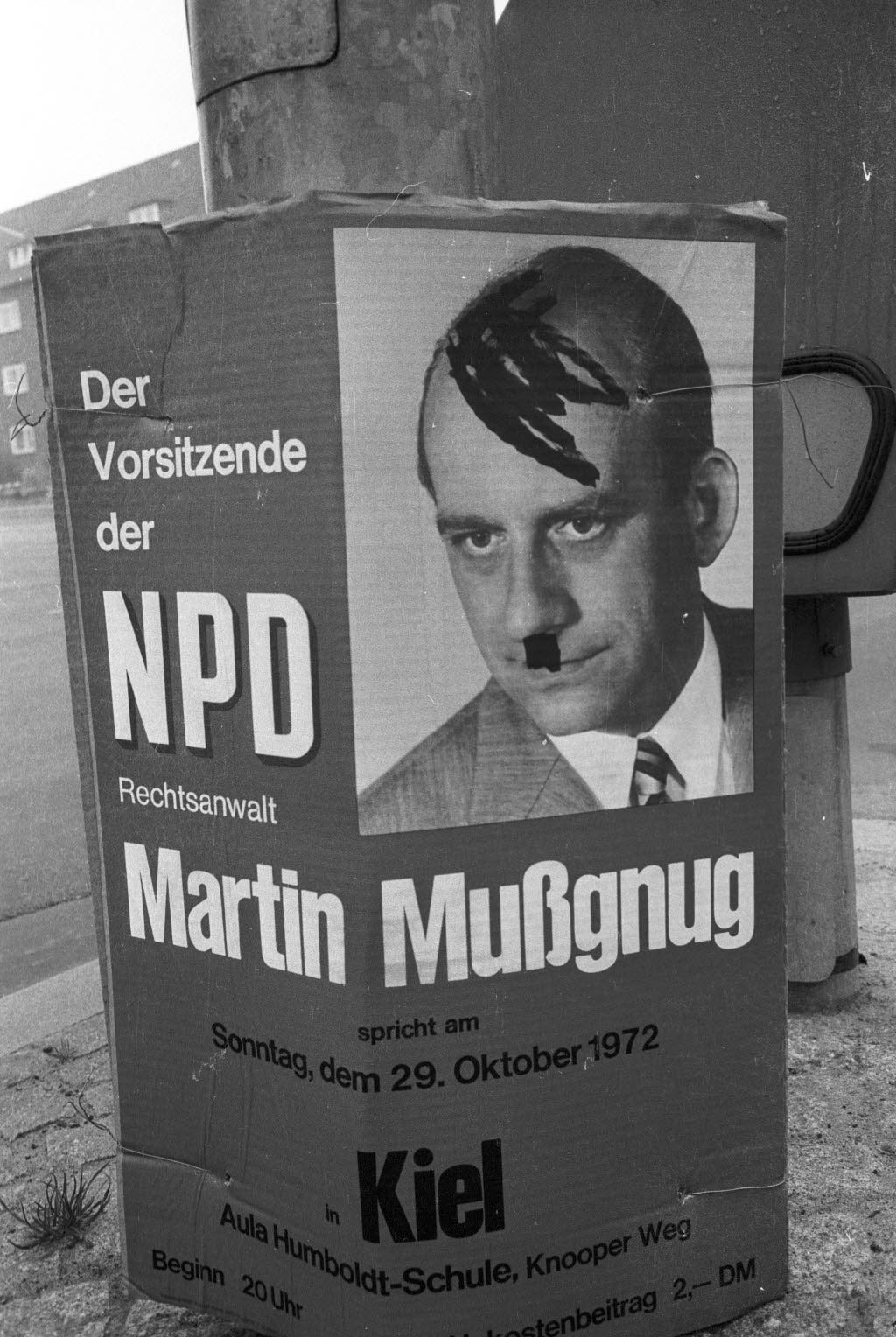

In 2001, the Gerhard Schröder’s government asked the Constitutional Court to ban the far-right National Democratic Party (NPD). Despite the fact that the party openly advocates “repatriating” all foreigners, it is still doubtful that there was enough evidence against them to meet the high legal hurdles required for a ban. But that proved to be irrelevant.

It turned out that the NPD leader in North Rhine-Westphalia, his deputy, and the editor of the party propaganda organ were all in the pay of the Verfassungsschutz. They were so-called V-Männer (informants), whom the spy service said they needed in order to keep tabs on the neo-fascists.

But the Constitutional Court judges found that it was no longer clear “to what extent the NDP are a state controlled party.” In other words, it wasn’t completely clear whether they were extremist out of conviction or because they were being incited to do so by their handlers.

The NDP are still around today, despite repeated attempts to ban them.

The law makes clear that the BfV’s informants cannot be people of influence inside the organization that is being observed. But there is an obvious contradiction here: if the person doesn’t have real influence, then they’re not going to be in the room when the plans to overthrow the government are being made.

Case against the AfD

In recent weeks leading media outlets have made the case for classifying the AfD as a Verdachstfall. An editorial in Der Spiegel declared that “those who attack democracy must be put in their place. The AfD has brought this decision on itself, even in an election year.”

The magazine specifically mentions the birth pains of the Bundesrepublik as justifying the move:

“Germany is a ‘resistant democracy’ because the mothers and fathers of the Constitution learned lessons from the failure of the Weimar Republic. When democratic freedoms are used against the democratic order, protection of the system counts more than individual freedoms.”

But asking whether the AfD is an enemy of democracy or not seems to be missing the point. More important is surely the question of whether it is the job of a politically controlled agency to find this out.

Such a process is never going to be seen as impartial by the 5 million or so people who vote AfD.

The government could apply to the Constitutional Court for a ban. The fact that they are choosing the murky route of spying rather than presenting their case to the Constitutional Court suggests that they aren’t confident they’d win.

Perhaps the AfD are a scourge on German democracy. But it is the job of political parties to beat them fairly and squarely at the ballot box. If they have become so radical that they need to be controlled in other ways, that is surely the job of prosecutors and judges.

Like what you’re reading? Share with friends

And rightly so ….

Kanzler Merz is a strong Leader in Germany for Europe ❤️

No defense for AfD extremist.

Election is over Democracy won.