End of the Brandmauer, Part II

Has the time come for the CDU to start talking to the AfD?

Dear Reader,

A debate has flared up inside the CDU over whether the centre-right party needs to reconsider its current policy of boycotting all forms of cooperation with the AfD.

Up until now, the CDU and its sister party, Bavaria’s CSU, have ruled out coalitions with their hard-right competitor. A resolution passed by the CDU at their 2018 party conference even put this into writing — it states that the party “rejects any coalitions or similar forms of cooperation with the AfD.”

This boycott, colloquially referred to as the Brandmauer (“firewall”), is aimed at keeping the AfD out of power at all costs. It is also a strategy shaped by the rise of the AfD itself: the calculation has long been that, by making clear the party stands no chance of entering government, voters might be discouraged from “wasting” their ballots on it.

That hasn’t happened. The Brandmauer has been in place for a decade, yet the AfD keeps getting stronger. In national polling, they have been level with or ahead of the CDU on around 26 percent for months. Meanwhile, polls for two upcoming state elections predict thumping AfD victories. In Saxony-Anhalt, the hard-right party is polling at 40 percent — well ahead of the CDU on 26 percent — ahead of an election next September. In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (also voting next September), the AfD leads on 38 percent, with the SPD a distant second at 19 percent. In both states, the AfD are only a few points short of an outright majority — a highly unusual scenario in Germany’s PR voting system. At the very least, attempts to keep the AfD out of power would require the CDU to work with Die Linke, the successor to East Germany’s communist SED — another party they have vowed never to cooperate with.

On one hand, the Brandmauer may become redundant in parts of the country if the AfD simply wins outright majorities. On the other, upholding it might force the CDU ever further to the left.

It’s an open secret that many regional CDU members are deeply dissatisfied with the Brandmauer, which they see as counterproductive. The main criticism is that it effectively makes the CDU a hostage to left-wing parties: because it bars cooperation with the only other party on the right, it forces them to seek compromises with progressives — something the SPD and Greens know how to exploit.

Now, those pushing for a course correction have found an unlikely ally. Peter Tauber — Angela Merkel’s right-hand man for many years — served as CDU party secretary between 2013 and 2018 and was one of the architects of the Brandmauer. Yet, last week he gave a series of interviews arguing that it was time for the CDU to change course. In an interview with Stern magazine, Tauber said the CDU should ditch the firewall and instead “adopt a policy of red lines that also allows decisions to be made that the AfD agrees with.”

Tauber then followed up with another interview in which he lamented the fact that the CDU had trapped itself in a “Babylonian imprisonment,” with left-wing competitors holding the keys to the jail cell. “If we don’t free ourselves, then sooner or later the CDU will cease to exist,” he warned dramatically.

But he wasn’t done there. Tauber said the Brandmauer debate had become so toxic that it now threatened to destabilise the entire political system. “If we can’t calm the debate down — if we can’t get back to arguing over actual policies — then the doomsday scenarios that some people are predicting for the Republic are, unfortunately, much closer than we think,” he stated.

Advertisement:

What’s the reaction been?

At first, Tauber’s intervention appeared to be an “emperor has no clothes” moment. As soon as he had spoken, CDU leaders from eastern states rushed in to agree that the Brandmauer needed to go. Andreas Bühl, CDU faction leader in the Thuringia, said that “it is okay to pass laws that we consider to be good based on votes from the fringes.” The CDU in Saxony agreed that “regardless of Brandmauer discussions, we should follow through on our own policies.” Saskia Ludwig, a Bundestag lawmaker from Brandenburg, suggested that at the state level the CDU should consider forming minority governments and passing laws with AfD support if necessary.

But the discussion quickly revealed just how divided the CDU/CSU remains on this deeply emotional issue. “The AfD are a danger to our country — they are opponents of NATO, want to leave the EU and move closer to Putin,” retorted Martin Huber, party secretary of the CSU (the Bavarian equivalent of the CDU). Using similarly apocalyptic to Tauber’s, he cautioned that “working with the AfD would destroy us.”

Daniel Günther, state leader of Schleswig-Holstein, also rejected a change in course. “Anyone who mentions the CDU and the AfD in the same breath has not understood what it means to be conservative,” he said.

What comes next?

This isn’t the first time the CDU has argued over the limits of the Brandmauer. Two weeks before the last election, Friedrich Merz made his own attempt to soften its foundations.

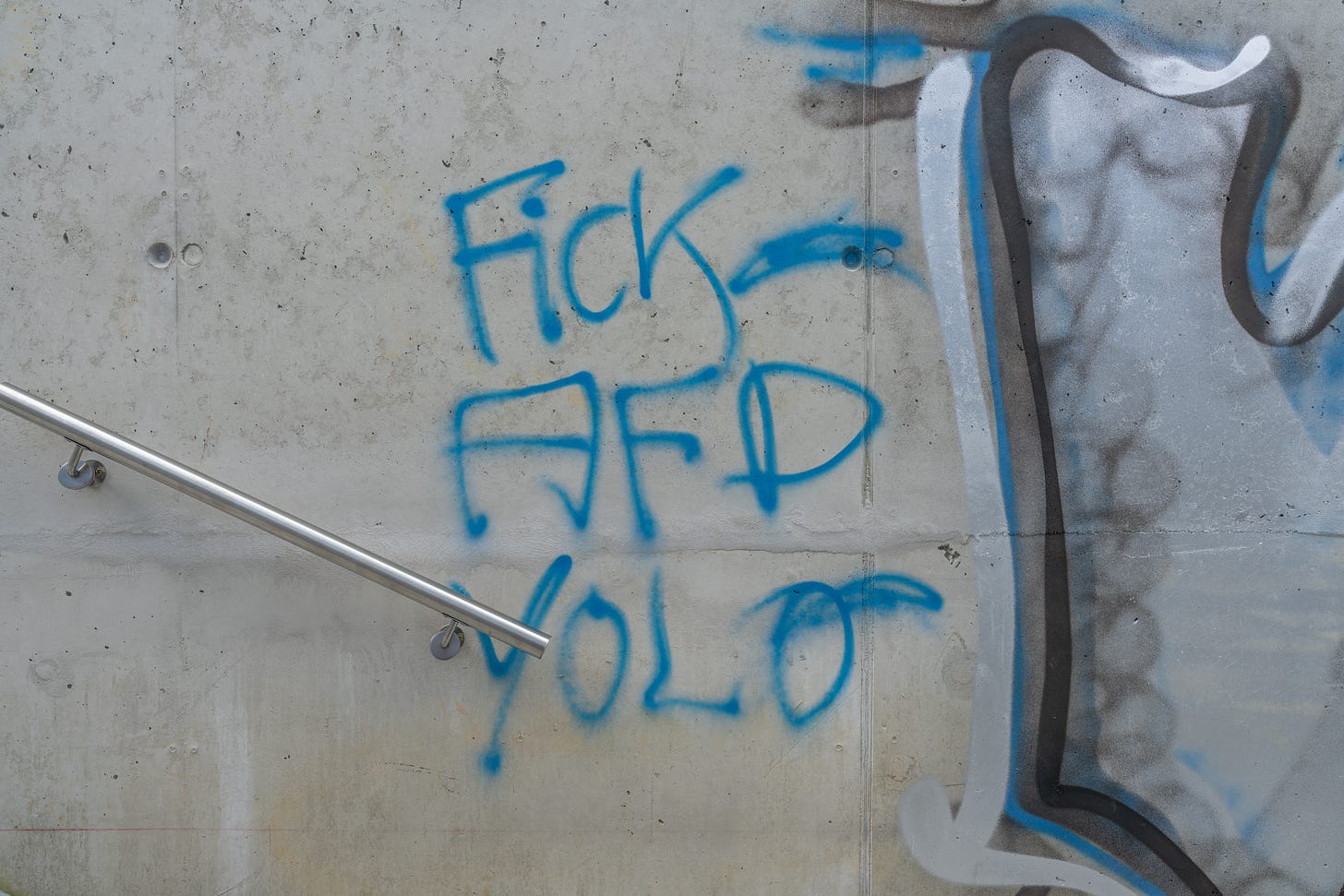

In the wake of the murder of a young boy by an Afghan migrant, Merz — still opposition leader at the time — sought to push through tougher migration rules and made clear that he was prepared to rely on AfD votes to secure a majority. The move triggered heated Bundestag debates filled with references to 1933. Tens of thousands took to the streets to protest against Merz. Activists even broke into CDU offices to hang out banners warning of a return to Nazism.

Whatever Merz’s plan was, it failed miserably. Enough members of his own caucus rebelled to hand him a humiliating parliamentary defeat — with the AfD the only party that solidly backed him.

That episode burned Merz’s fingers. Speaking this Monday, he tried to put a lid on the debate. Dismissing those calling for an end to the boycott as “fringe figures,” he insisted that no common ground exists between the CDU and the AfD.

Instead, he said that his approach would be to start treating the AfD as his “chief rival.” “When we designate someone as our main opponent, then we really fight them,” he declared.

Two years ago “there was speculation” that the Greens would win the next election, he recalled at Monday’s press conference. That prompted him to designate the eco-party his “chief rival” and focus all his energy on putting them back in their place. The Greens’ poor election result, he implied, was proof that the strategy worked.

In other words, those in the CDU calling for an end to the Brandmauer are panicking: all it will take to put a dent in the AfD’s popularity is for Merz to get into the ring with them.

The German Review’s take

Merz’ less than convincing win at the federal election seems to have gone to his head. When he designated the Greens his “chief rival” two years ago, he was joining a public pile-on that followed the eco-party’s ill-fated attempt to ban gas heating. The Greens were already polling at around 14 percent. There is little evidence that anything he did or said accelerated their decline.

The key difference is that the Greens were in power, meaning their policies were tested — and found wanting. As long as the AfD remains outside government, even at state level, they can maintain the illusion that they would do everything better.

As I wrote shortly after the election, it would be far wiser for the CDU to adopt a red lines approach to their hard-right rival. Whatever Merz claims, objective analysis of party programmes shows that the CDU’s policies are most closely aligned with those of the AfD — in every area except foreign policy.

Offering the AfD the carrot of participation in government — on the strict condition that they back NATO and Ukraine unequivocally — would put the ball back in their court. Either they would walk away and demonstrate that they have no genuine interest in governing, or they would be forced to moderate.

Last week’s poll: Are German unemployment benefits too generous?

Yes - 49%

No - 34%

They get the balance right - 16%

News in Brief

✈️Germany has deported criminals to Syria for the first time since the outbreak of its civil war fourteen years ago. The deportations are being described as “consensual,” having taken place ahead of an expected deal between Berlin and Damascus on returning people who fled the country’s devastating conflict. The state government in Baden-Württemberg persuaded 13 members of a Syrian family with the offer of €1,350 each in “starter cash” plus the threat that they would be on one of the first planes back home once the deportation deal was in place. The family terrorised Stuttgart’s city centre over years, accumulating well over 100 convictions, including for stabbings and attempted murder.

🪖In an echo of the quarrelling that typified the former “traffic light” coalition, the Merz government is struggling to conceal its differences over plans to bring back military conscription. A press conference to announce the new plans was cancelled at short notice after Defence Minister Boris Pistorius (SPD) reportedly flew off the handle over changes made to the draft law without his knowledge. The CDU want young men to be conscripted through a lottery system, while the SPD say all 18-year-old males should fill out a form detailing their fitness and willingness to serve — but want them to be able to decide for themselves whether they ultimately join up.

👨🦲 After months of silence, Olaf Scholz has given his first interview since leaving the chancellery. While his foreign minister jetted off to New York to head the UN General Assembly, his economy minister took up a teaching role at Berkeley, and his finance minister became a startup investor, Scholz retired to a quiet life as a backbench MP. Although major media outlets would have given anything to publish his first post-chancellery interview, he instead gave it to a low-budget podcast. Anyone hoping to hear an unchained Scholz dish the dirt on three years of ego-fuelled Ampel chaos will be disappointed. A walking lexicon of the German legal code, Scholz will go down in history as the ultimate anti-populist. Unfortunately for him, dry lectures on legal small print are not a recipe for electoral success.

Members’ corner

We’re reading:

Handpicked Berlin - tech, startup and career news for Berlin

Kaffee+Kuchen - musings on expat life in Germany

20% Berlin - local Berlin news in English

Share The German Review with friends to win a free subscription

Sincerely,

Jörg Luyken

Seems to me that the Americans had a point about silencing/refusing to work with people of different opinions is anti-democratic. Cancel culture is childish and does not resolve anything. Focusing on identity diverts attention from policy and actions. AfD supporters might not care about the name calling as much as about the Policy proposals. If doing is more important than spouting ideological propaganda then the electorate is offered a range of Policy solutions/options... Instead of virtue signalling and words that cannot be backed with action....Like deciding what should happen in Ukraine instead of working on what should happen in Germany...

Hopefully.