Will a new Left-wing party shake up German politics?

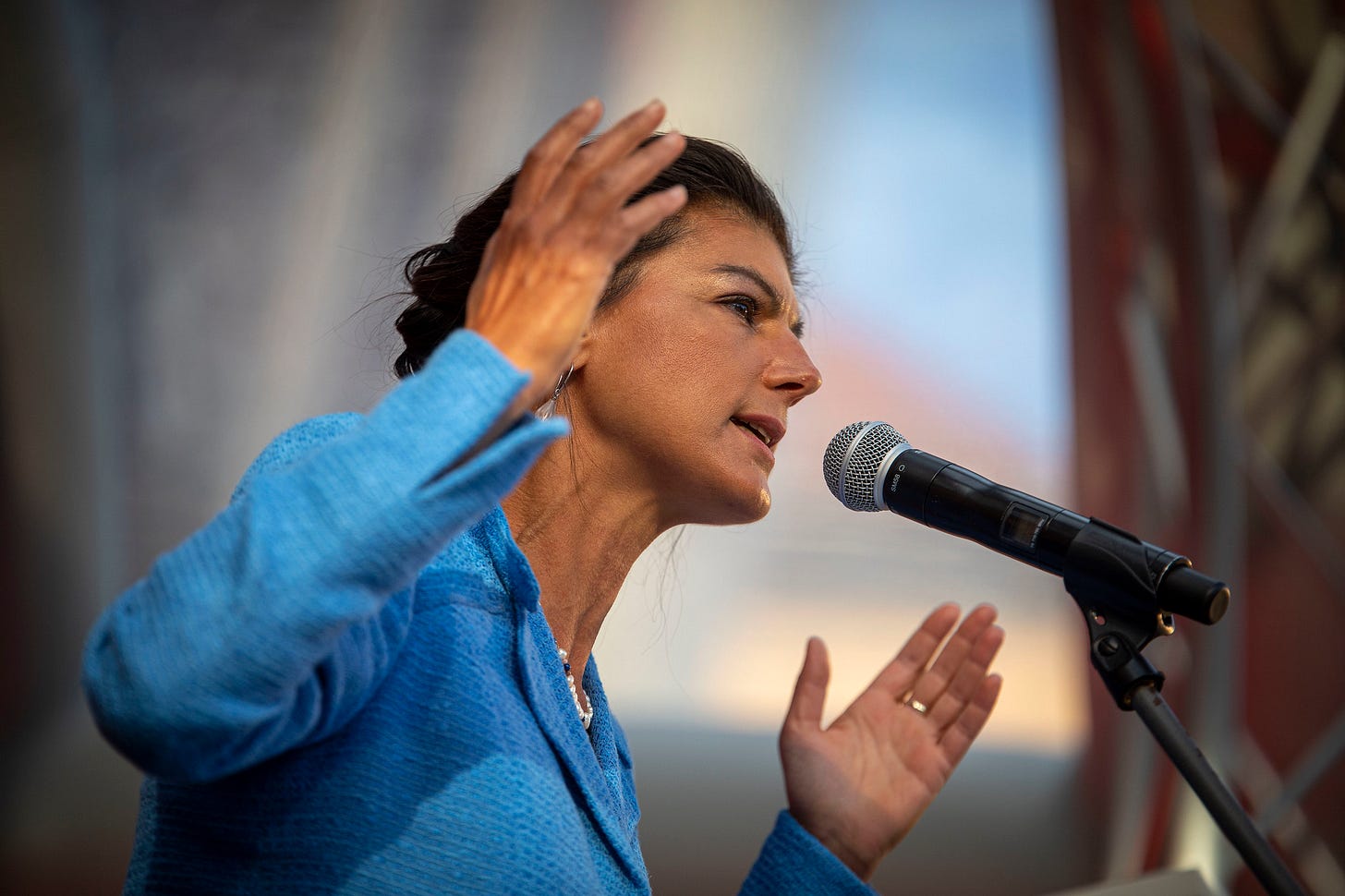

Sahra Wagenknecht is about to set up a new party that combines left-wing social policies with a hard line on immigration. Will she have success?

Dear Reader,

Something quite fascinating is going to take place on Monday which could have far-reaching consequences for the future of German politics... or it could be a damp squib.

While it is still too early to tell just what impact a press conference announced by left-wing firebrand Sahra Wagenknecht will be, one thing is certain: her statements at the Bundespressekonferenz will rattle rivals from across the political spectrum.

It appears highly likely that Ms. Wagenknecht will announce the establishment of a new political party. She has already registered a political organization called the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW), and it's difficult to discern any other purpose for the press conference than launching a new political movement.

Few German politicians can match Wagenknecht for name recognition. The daughter of a German mother and an Iranian father who grew up on the east side of the Berlin Wall, she is one of a handful of active politicians who is a household name. Articulate, glamorous, and unwaveringly self-confident, Wagenknecht stands out in a crowd of largely grey politicians. She is anything but media-shy. Turn on your television in the evening, and you are likely to find her on the couch of one of Germany's plethora of political talk shows.

She is officially a member of the hard-left Linke party but has been relegated to the backbenches after losing a power struggle with a younger generation several years ago.

But these politicians, who appeal to inner-city hipsters, failed in their attempt to sideline the woman once seen as the natural heir to Rosa Luxemburg. Instead, she wrote books, toured the country, and set up a successful YouTube channel. All of these projects were aimed at challenging what she sees as the stifling political correctness that has alienated the party from its working-class voting base.

Here is Wagenknecht in hero own words on political correctness:

"The fact that people today can enter into same-sex partnerships and have the same rights is a great success. But when gender theory tries to make us believe that there are no biological differences between men and women, that is bizarre, to say the least. The same applies to when anti-racism is understood to mean that skin colour determines what someone is allowed to talk about."

"Gender asterisks and other language distortions certainly do not determine whether women receive the same wages as men... This artificial language is itself exclusionary. Many people with concerns other than dealing with the ever-changing rules of correct speech are deprived of their language because their way of expressing themselves is made contemptible."

In other words, Wagenknecht talks sense about things that voters care quite a bit about. And she is one of the few voices on the Left willing to do so.

But there's another, more thorny side to her worldview.

Raised in the GDR, Wagenknecht remains reflexively anti-American. She has repeatedly blamed the US for the Russian invasion of Ukraine and regularly promotes the theory that the US orchestrated the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines. Lacking any concrete evidence, she instead claims that, since German prosecutors have reportedly linked the sabotage to the Ukrainian army, "the simple truth is that Ukraine doesn't do anything that the US doesn't want them to, as they simply can't afford to."

Perhaps she is straying into the realm of conspiracy theory there. Hard to tell. But her views on the wider implications of the Nord Stream sabotage should be taken more seriously. I think they will become increasingly relevant in the coming years.

While Olaf Scholz and his government insist that a golden age of cheap energy is on the horizon as soon as enough LNG terminals, wind turbines, and solar farms are built, Wagenknecht argues that German economic success is inextricably linked to Russian energy imports.

In a nutshell, she argues that the alternative to Russian gas is US gas. But Germany and the US are competitors on industrial production so the US has no interest in selling Germany cheap energy. (I think that we only need to look at the breakdown in talks on custom duties between the EU and Washington this week to see that this is true.)

The Ifo Institute, Germany's leading economic think tank, largely agrees. It has rejected Berlin's proposal to introduce a temporary energy subsidy for heavy industry because "electricity costs in Germany will be permanently higher than in many other countries."

In other words, contrary to the government's claim that the rise in energy prices is a blip, uncompetitive costs are here to stay. A temporary subsidy would become permanent.

Where the Ifo Institute and Wagenknecht dioverge of course is on their solutions. Wagenknecht wants to reopen the Nord Stream pipeline that wasn't hit by the saboteurs and to repair the other three.

The Ifo Institute would never back such a politically explosive solution. Instead, its chief economist, Clemens Fuest, suggests that "Germany should not cling to structures that are no longer competitive" - i.e. - it should wave goodbye to energy-intensive industries like chemical processing, which have been the backbone of German wealth for decades.

Fuest's stance is that the solution lies in cutting welfare payments and bureaucracy to attract new industries. “The good news is that economic and fiscal policy certainly has the means to create conditions that will allow these challenges to be met," he says optimistically.

However, it remains unclear which new industries he is referring to and whether the German workforce can be retrained for them.

For Wagenknecht, Germany's future presents a starker choice: continued wealth or continued adversary with Russia.

I haven't found recent polls which gauge Germans' support for a Russian energy boycott. Back in 2022, a majority did support such a boycott. However, much has changed since then, particularly the fact that the front in Eastern Ukraine provides little hope that the war will end in a defeat of Russia on the battlefield any time soon.

What we do know from polling is that approximately 20 percent of Germans could envision voting for a Wagenknecht party - and those votes are likely to come from every party from the far-Right AfD all the way to the hard-left Linke.

Furthermore, the recent state elections in Bavaria and Hesse showed us just how angry Germans are with their current leadership.

Much remains uncertain. At the moment, a flatlining economy has had little impact on the labour market. But mass redundancies in the industrial sector, if they were to come, would almost certainly benefit one person above all: Ms Wagenknecht.