Why flooding in Germany is getting worse

German rivers large and small have burst their banks in recent years, causing billions of euros in damage. What is behind the seeming uptick in such disasters?

Dear Reader,

Germany’s mighty rivers, the Rhine in the west, the Danube in the south and the Elbe in the north, brought prosperity to local merchants in the middle ages.

But they were also a threat to the wealthy trading towns that were built on their banks.

One of the most vivid reminders of the destruction these forces of nature can wreak is a series of markings at the entrance to Schloss Pillnitz in Dresden. These record high water marks on the River Elbe all the way back into the 18th century.

The highest markings, from 2002 and 1845, almost reach the top of the sandstone gate. (Eerily, the Elbe also has records of low water marks, so-called ‘hunger stones’ that record years of drought.)

On the Elbe - which flows from the Riesengebirge in the Czech Republic, through the Saxonian states, Hamburg and into the North Sea - people have been building dykes to hold back floods for at least 800 years.

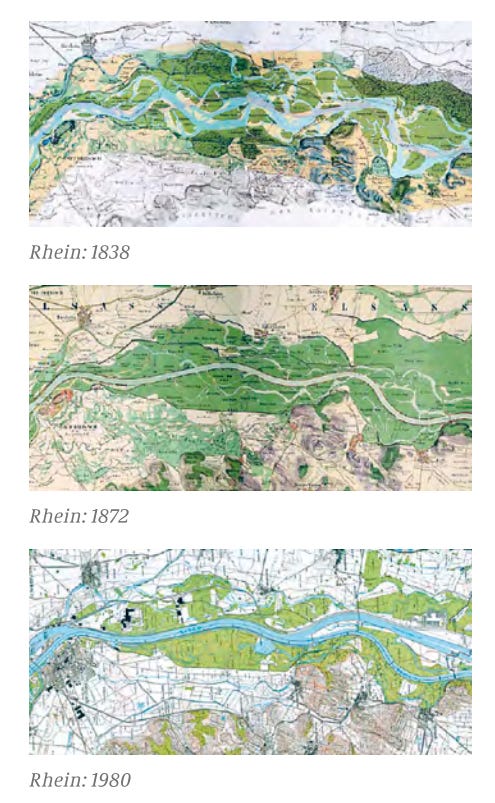

In the southwest, chronic flooding in the upper regions of the Rhine provided the impetus for “the greatest feat of engineering in German history” - the straightening of the Rhine by engineer Johann Gottfried Tulla.

Proclaiming that “a river only needs one bed,” Tulla eliminated the river’s multiple branches, deepened the river bed and constructed a system of dams on its upper reaches.

These modifications appeared to solve the problem of flooding, while also making the river passable to shipping all the way up to the Swiss city of Basel.

But Tulla’s immense feat came with long-term costs, both environmental and in terms of safety. The project eradicated almost all of the river’s floodplains. This wasn’t just a disaster for the local ecosystem, it also lured humans into a false sense of security. Protected by dykes, people settled the plains and started to till the land.

The straightening of the river also increased its speed. Flood crests are now faster and higher, according to the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine. A flood wave that used to take close to three days to travel from Basel to Karlsruhe, now gets there in less than 24 hours.

Only after the Rhine was hit by two ‘once in a century’ floods in the 1990s, causing millions of euros of damage to cities like Koblenz and Bonn, did German authorities realise the need to take measures to calm such surges.

The Elbe was subjected to similar efforts to tame it and make it more passable to shipping. It has lost 70 kilometres of its length, while its flood plains have been shorn from 6,000 square kilometres at the beginning of the 19th century to 8,000 today.

Across the country, where rivers have been “tamed” in similar ways, people have moved into the floodplains. Over a quarter of a million homes are now built on floodplains, according to the National Association of Insurers.

Dykes have been constructed to hold the waters back in case of emergency. But they can never provide 100 percent security.

In a report published in 2012, the Federal Environmental Agency warned:

“Dyke construction is an integral part of comprehensive flood risk management. Nevertheless, floods can occur that overtax their capacity. The damage would then be severe. Despite technical solutions, the state cannot guarantee absolute safety.”

So, what can be done to protect people living next to these unpredictable forces of nature?

There are fairly low cost ways of reducing the damage once the levees have been breached: houses can be built without cellars; washing machines can be put on stilts; oil heating systems can be banned to prevent water pollution. Warn Apps are already alerting people to impending evacuations.

But policies that would reduce the chances of catastrophic flood surges sweeping through towns in the first place are much harder to implement.

Experts agree on the need to reintroduce floodplains. But land that once provided breeding ground for birds, insects and diseases now belongs to someone else.

The farming lobby have rejected efforts to give fields back to the rivers, claiming that it is nature preservation dressed up as flood management.

Meanwhile, some experts have suggested in recent days that we should consider demolishing some settlements. That just seems fanciful.

Since 2012 the construction of new settlements on flood plains has effectively been banned. Soberingly though, an assessment published by the National Insurers’ Association last year found that an average of over 2,000 homes were still being built on floodplains every year.

Still, on the river Elbe, it’s not all bad news.

On Boxing Day I drove through flooded forests to the east of the city of Dessau in Saxony-Anhalt. The trees there had been swamped by the Elbe’s surging tide. But that wasn’t a bad thing. The area is a UNESCO-protected nature reserve. Flooding is actually key to ensuring the survival of its diverse flora and fauna.

On the other side, the streets of Dessau - protected by an immense dyke - remained nice and dry.

Hmmm I had to read it twice, it seems you forgot to blame climate change for all of this - LOL your point about building on flood plains is absolutely correct - much of it related to man trying to tame nature. Speaking of nature Diane Francis wrote a great article to quote (link below)

Hysteria aside, extreme weather events throughout history — from ice ages to heat waves -- have been triggered by non-human volcanic or orbital activities. And this year is no exception. In March, scientific journal Eos revealed that this summer’s heat, are the result of a gigantic underwater volcanic eruption in January near the tiny Pacific Island of Tonga. Scientists estimate this explosion alone will be a major contributor to an increase in global temperatures for the next five years. Coverage on this was scant, as is the fact that there are at least one million underwater volcanos, and other natural phenomena, that greatly affect climate and always have. Political hysteria isn’t helpful. Humanity is to blame to a certain extent, but Mother Nature is mostly in charge.

Great summary and timely as always. Which raises a couple of questions and observations, Jörg.

Questions -

1. As you mentioned, restoring floodplains somewhere would be ideal - do you think after these floods, it may be easier to buy some farms out, or at least offer insurance to certain farmers in specific areas, such that fields can be allowed to flood if necessary?

2. Since property losses per flooding event are rising globally, typically because more people manage to keep building in floodplains (you noted that as of 2012, it’s difficult to build in floodplains but still 2000 households per year do), do you think that flood insurance will become prohibitively expensive or impossible to get for any buildings in flood plains?

3. What will be the political impacts be if flooding events become more frequent and severe (because the models show there will be more prolonged droughts, dry soils hold less water when you get the same amount of rain, a warmer atmosphere holds more water (7% per degree), etc.)?

4. Is it politically feasible to pay for infrastructure upgrades for roads and rail to prevent catastrophic destruction (like what happened in the Ahr Valley)?