Germany’s China Dilemma: Profits, Power and Moral Blindness

Germany’s economic relationship with China has delivered enormous profits — but at what moral and strategic cost? An examination of trade, power and political denial.

We don’t need to tell you that China is a pretty big deal these days. The People’s Republic’s economy has grown fourteen-fold since the turn of the century; it took over the US as the world’s major trader years ago. China is now a superpower.

But for Germany, China is above all a place to make money. Lots of money. Anyone who has visited Beijing in recent years can hardly have failed to spot the armada of Volkswagens and Mercedes drifting through its smoggy streets.

But there’s one problem. China’s communist party is attempting to snuff out democracy in Hong Kong, is intimidating Taiwan, and has locked up, tortured and attempted to indoctrinate up to a million Muslims from the minority Uighur population in the north-western Xinjiang province.

Berlin has squared the circle of deepening ties with this unethical regime with the rather neat formula of Wandel durch Handel. Meaning “transformation through trade”, this concept was first applied to relations with Eastern Europe during the Cold War. One of Merkel’s closest confidants, economy minister Peter Altmaier, is convinced it can also work in the Far East.

Sceptics say that the concept is a convenient veil for a foreign policy designed to enrich Germany’s biggest firms. At the very least, evidence of Wandel inside China (at least any for the better) seems vanishingly thin.

Not everyone agrees that Merkel solely sees herself as an ambassador for German business. China expert Noah Barkin argues that the cautious Chancellor fears what would happen if western states decided to yank the dragon’s tail. Economic integration, even if it fails to make China more liberal, at least makes it more predictable. In this interpretation, VW sedans are trojan horses in a strategy of sedating the Chinese upper classes with the trinkets of capitalism.

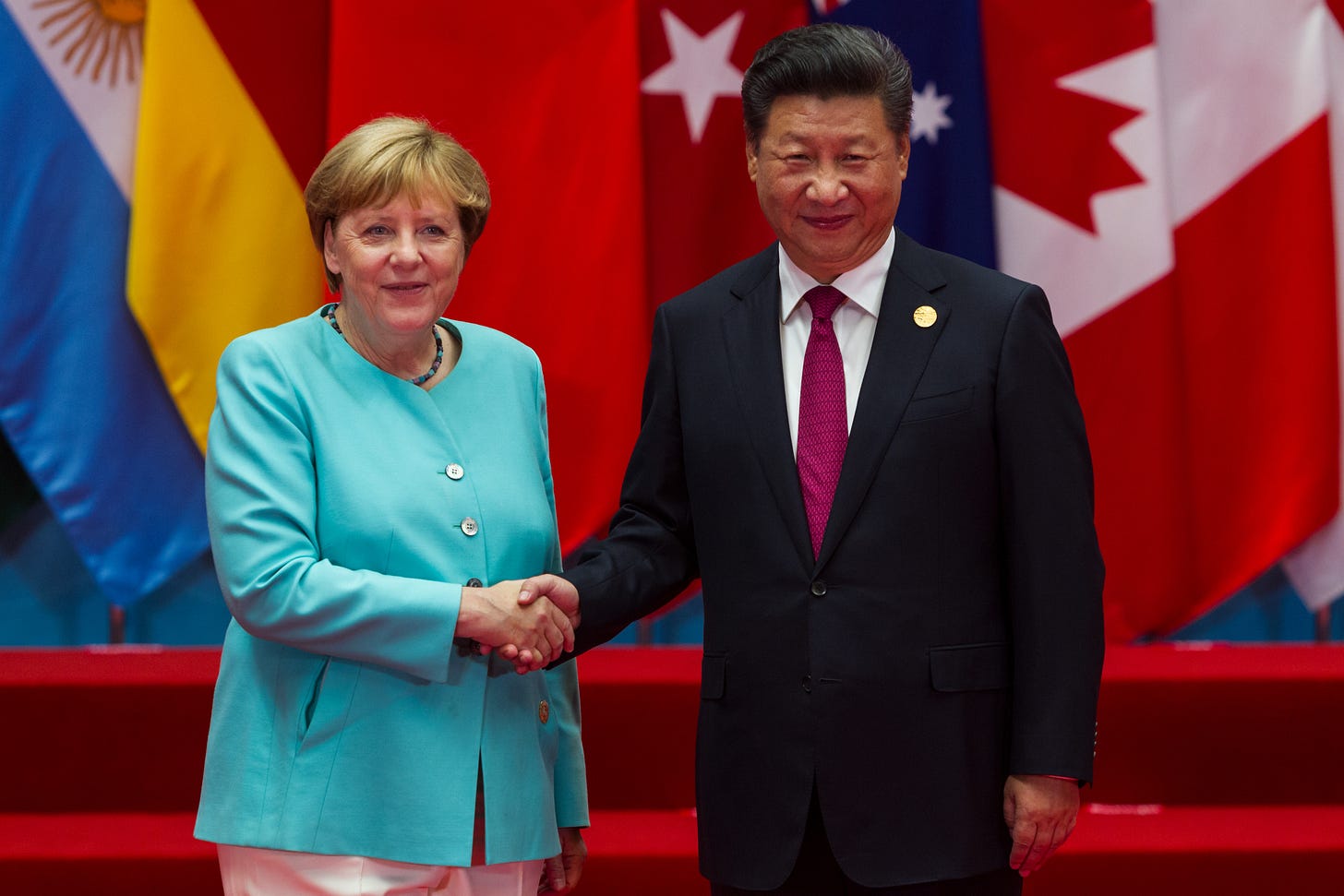

Merkel has certainly stood her ground on this trade-first approach even as international criticism has grown. One of her final acts of foreign policy was the agreement of an investment pact between Beijing and the EU in the last days of Germany’s EU presidency in late December. That pact will further cement business ties, making it harder for the next German government to - in US jargon - “decouple” from China.

While the EU claims that the investment deal compels China to eradicate forced labour, the Communist regime doesn’t seem to have noticed that part.

A brief history of Merkel in Beijing

Two events over the past year exemplify how Angela Merkel has approached relations with Beijing during her time in power.

In early April, while governments engaged in a mad rush to buy up medical masks, Merkel called up Chinese premier Xi Jinping to ask for a favour. Germany needed more masks, could he step in to ensure her country was at the front of the queue? He gladly complied.

Three months later, when the Chinese People’ Congress introduced a new “security law” for Hong Kong giving it powers to lock up political dissidents, Merkel kept quiet while Washington and London took concrete diplomatic countermeasures.

Merkel wasn’t always so adept, but she learned fast. After welcoming the Dalai Lama to the Chancellery in 2007, she was criticized not just by Beijing but by own her foreign minister (and the current “spiritual leader” of Germany) Frank Walter Steinmeier, who worried about hurting Chinese feelings. Merkel has been careful to say the bear minimum on issues like Tibet, Hong Kong or Xinjiang ever since.

In return, Beijing has happily used its propaganda channels to portray Merkel as the dependable European. Whenever she visits the country, she can always expect a warm reception from the Chinese public.

Given the smiling crowds, perhaps it’s no surprise that she goes back so regularly. Since her first trip in May 2006, the veteran Chancellor has been back 12 times. That’s more visits than to neighbouring Austria (8), and far more than to the major Asian democracies, Japan (six times), India (4), and South Korea (2).

Whenever Merkel visits Beijing, she is always flanked by a cohort of CEOs. During her last trip in 2019 she brought along airline execs, bankers and electronics firms. She even invited the bin men. The prize was eleven co-operation contracts signed with Chinese companies.

Trade with China in numbers

Back in 2016 China overtook the US as Germany’s single largest trading partner. In 2019 a combined 206 billion euros in trade was conducted between the two countries.

As the Chinese middle classes explode in size, so does the demand for German products. The value of German exports has risen from €30 billion back in 2007 to close to €100 billion today. Car sales make up the biggest slice of this export boom.

During the corona pandemic, the importance of China to Germany’s export-heavy economy has only increased. As trade with European neighbours and the US slumped in the autumn, sales to China stayed stable. Trade specialists predict that China will be key to hauling Germany out of the corona crisis this year.

While these headline numbers are often used to explain Merkel’s soft approach to Beijing, some important context is often forgotten. Exports to China still only make up 7 percent of the total, behind the US at 9 percent and way behind the EU as a whole at 69 percent.

The Auto lobby

The German car giants Volkswagen, Daimler and BMW have taken on the role of the three wise monkeys in China.

Volkswagen’s feigned ignorance of human rights abuse is the most staggering.

VW built its first car in China back in the 1980s and now has 33 factories spread across the country producing over 4 million cars a year. The Wolfsburg firm describes itself as “China’s most dependable partner.” Dependable indeed. Asked by a BBC journalist if he knew about the “re-education camps” in Xinjiang province, where VW operates a factory, CEO Herbert Diess claimed he was “not aware” of their existence.

BMW is also in the process of a major expansion that will raise their production in China to over 600,000 units a year. The Bavarian firm last year was forced to deny allegations it was implicit in forced labour of Uighur Muslims.

Daimler, whose mega-factory in Beijing is the jewel in a crown of 30 global plants, had its own Dalai Lama moment in 2018 when its social media department published a bit of Tibetan wisdom on Instagram. The quote “look at situations from all angles and you will become more open” was online for a brief few hours before it was deleted. Daimler then wrote on Chinese website Weibo that it promised to “immediately take concrete steps to deepen our understanding of China’s culture and its values.” (Perhaps they should ask Mr Diess the directions to the nearest re-education camp.)

You won’t be surprised to learn that the German Association of the Automotive Industry has applauded the EU-China investment pact for the opportunities it opens up, and says it should be ratified as soon as possible.

The end of ambivalence?

When Daimler was asked by a German journalist why it grovelled to the Chinese Communist Party after its Dalai Lama faux pas, the firm responded that it had “respect for countries with different value systems.”

That sounds patently self-serving, but it is no different to the moral relativism recently fashionable in policy circles in Berlin. Some of the most influential experts in the German capital believe that challenging China on human rights is akin to reawakening 19th century imperialism.

In a paper published in 2012, the German Council on Foreign Relations - the country’s top foreign policy think tank - described human rights advocacy as an expression of “traditional western arrogance” that blocked acceptance of China “as an equal partner.”

News of mass arrests of democracy activists this month in Hong Kong makes such moral relativism ever less palatable. When Merkel retires this September German ambivalence towards human rights abuses is likely to go with her.

Several experts see a coalition developing across party lines that wants to pursue a more values-driven approach to China.

Writing in Der Spiegel last summer, Europe Minister Michael Roth (Social Democrats) warned that China was “a systemic rival” who “passes up no opportunity to drive a wedge between the EU member states and weaken them.” He called for the EU to use its trade power to push through its values abroad.

A similar policy is also advocated by Norbert Röttgen, a dark horse in the CDU leadership contest, which will be decided this weekend. Even business friendly Friedrich Merz, the favourite in the race, wants a more hawkish China strategy.

Then there are the Greens, the most likely junior coalition partners in the next government. The environmentalists have for years been demanding that red lines are laid down in front of the autocrats of Moscow and Beijing.

None of this means that we should expect a radical change in policy in September, experts say. The German population has no appetite for confrontation with China, and the export-driven economy has much to lose. But a change of administration in Washington offers an opportunity for western reconciliation. Maybe Daimler, VW & Co won’t be invited along on the first state visit to Beijing of Germany’s next Chancellor.

Thank you for clarifying this issue. This will hurt German workers in the long run big time. She should visit the American towns or neighborhoods destroyed by unhinged trade with China. They're also breeding grounds for Trumpism...