Germany's invisible Covid wall

This newsletter is a five minute read

Dear reader,

Today we are discussing the invisible wall that is stopping corona infections passing from the young to the old. What is the barrier built of and just how robust is it? Plus a roundup of the news.

Do you have feedback? email us at info@hochhaus.news

Happy Friday!

Jörg & Axel

Five things:

While the Nordstream row has been put to bed (all parties but the Greens are in favour of finishing the gas pipeline), another set of pipes under the Baltic sea is causing a stir. This week the Bundesverwaltungsgericht in Leipzig started processing some of the 12,000 complaints against the planned Fehmarn-Belt tunnel between Lolland (Denmark) and Fehmarn (Schleswig Holstein). On the Danish side the 46 complaints against one of largest infrastructure projects in European history were promptly rejected...

Schwarze Null? Try nine red zeros. To the horror of the fiscally conservative camp, finance minister Olaf Scholz is plunging Germany into ever more debt. Tax revenues won’t be enough to finance next year's €400 billion budget, hence Mr. Scholz will for the second year in a row stomp all over the holy grails of balanced budgets (die schwarze Null) and moderate net debt (die Schuldenbremse). 96 fresh billion Euros will be needed to plug the hole in 2021’s Bundeshaushalt.

This Wednesday, Volkswagen unveiled what might be the most important car in German history. The much lauded ID4 will compete head on with Tesla’s model Y in the lucrative crossover-SUV market. Hundreds of thousands of jobs depend on the German automotive industry not being left in the dust as the electric vehicle wave sweeps the world.

And jobs are just what Germany needs. While the economy has not been hit as hard as in Southern Europe, Germans are getting poorer. With average working hours falling, real wages have followed. The 4.7 percent drop in the second quarter is even worse than during the financial crisis.

This has been a tough week for the German police (see Wed. edition). The Munich force seem to have a different past time to that of their Nazi-pic sending colleagues in NRW. 21 officers stand accused of having helped themselves to a cocaine stash in an evidence room...

The invisible wall

Something has been puzzling me for some time now.

Germany has been in a “second wave” of coronavirus infections for 10 weeks. The numbers rose over the summer holidays, flatlined somewhat at the start of September, and then started to climb again last week.

The peculiar thing though, is that the virus seems to be spreading among younger people without leaping into the older generations. It’s as if some invisible barrier has been constructed, protecting vulnerable parts of society. This explains why cases that end in death have plummeted from 7 percent in mid-April to just 0.3 percent today.

Something is happening this time round that is very different to the start of the year.

Back then - according to current understanding - the virus travelled back from ski resorts with young people, triggering an epidemic among older friends, family and neighbours. It didn’t take long for hospital beds to fill up.

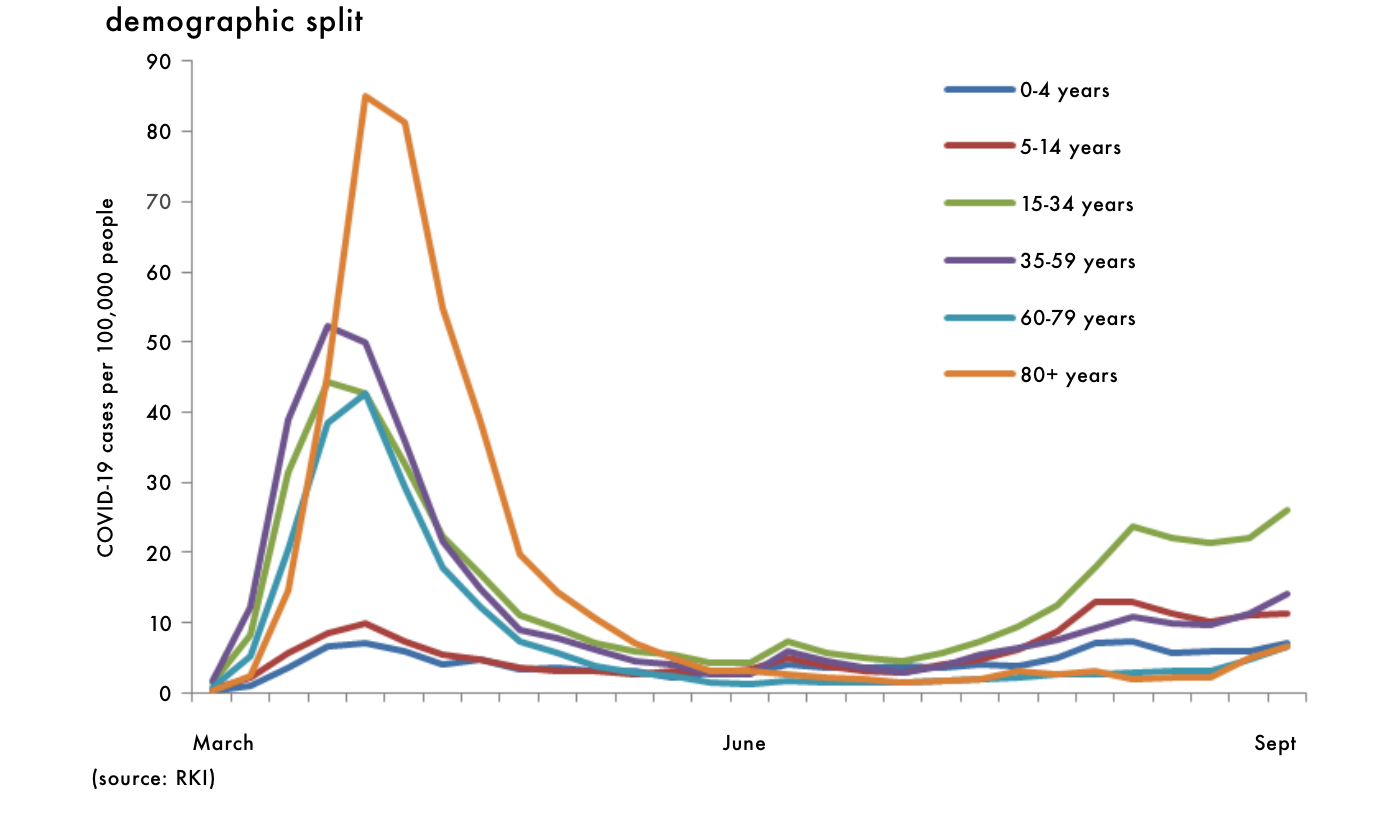

This time around cases began to rise in the age group 15-34 in late July, while flatlining in the 80+ category until September.

What’s causing this?

Getting an explanation from health authorities is harder than you’d think.

I first inquired with the Robert Koch Institute at the end of August. At the time they said that they had no “detailed explanation” but were monitoring the situation.

When I put it to them again this week they’d say only that “the disease is spreading among the young. If it becomes widespread in higher age groups, a further increase in severe disease progression and deaths must be expected.”

My complaint that this didn’t address my query went unanswered.

Among academics there is a consensus that two things have changed which are acting as a barrier: Behavioural habits and state rules.

Simply put, young people are still going out partying while the elderly have pulled down the blinds.

“I know many older people who are being very careful, who hardly ever leave the house. Events where older groups come together such as at concerts, theatre, and 80's birthday parties are now very limited,” Dr. Dittmer Ulf, director of virology at the Uniklinik in Essen told me in an email.

This is a point Dr. Berit Lange from the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research agrees with. "The fact that many young people have been infected up until now is above all due to behaviour,” she recently told Die Zeit. “They travel more. And at celebrations and family meetings it is possibly younger people who dare to meet in larger groups.”

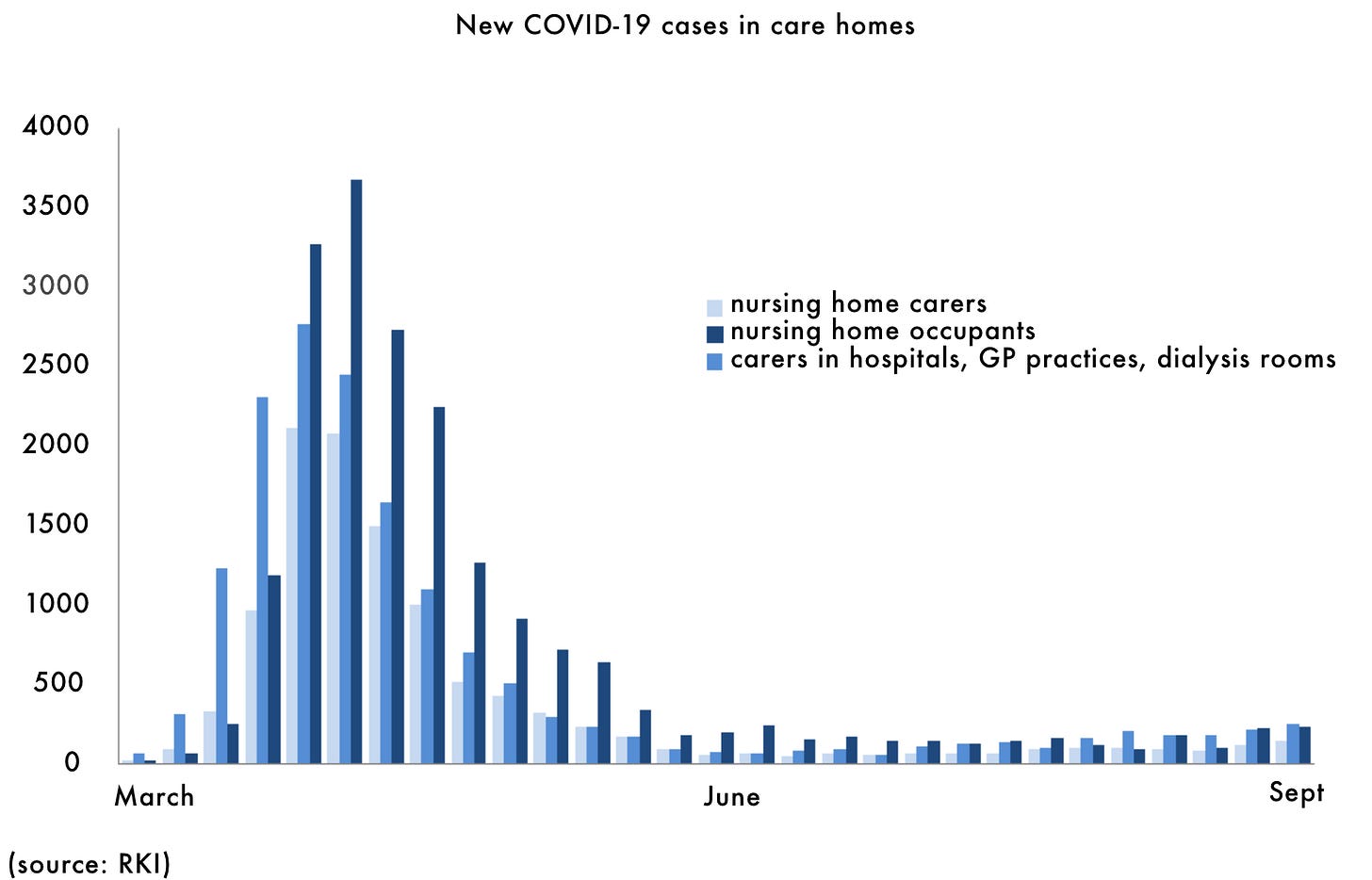

The second factor widely recognised as shielding the elderly is better protection at nursing homes and hospitals.

“At the beginning of the pandemic many old people were infected by younger people at work,” Dr. Dittmer explained. “For example in nursing homes, hospitals, and outpatient care, this ‘occupational’ transmission, which used to cause entire chains of infection, is now almost non-existent in Germany.”

As valid as these answers are, they don’t seem totally satisfying.

Over 70s in care facilities only make up a minority of people in that age group. Why are those who still live independent lives not becoming infected?

And yes, young people are more social - albeit to a much lesser extent than at the start of the pandemic. But older people still visit restaurants, travel on trains, and go shopping. Not all of them obey the rules on face masks.

Could something else be at work, too? I asked Dr. Dittmer, who researches immune responses, if older generations were receiving an element of protection from immunities they had developed over the course of their lives.

This could be the case, he said. “About 25-40% of the participants in various studies have had T-Cell or antibody responses against other corona viruses, which could also protect against SARS-CoV-2. The likelihood that such a response exists increases with age.”

But he also added that “this of course does not explain the different infection rates of elderly people in March/April compared to now.”

Prior immunity is a fascinating and under-reported aspect of the pandemic. For anyone interested, I recommend this article from the British Medical Journal on why research on prior immunity could radically alter how we understand and respond to Covid-19.

At this stage though, much about prior immunity remains speculative. Dr. Dittmer cautions that we only need to look at France and Spain, where hospitalisations, and even deaths, have started to rise again, to see that the invisible wall is far from stable.

J.L.

If this newsletter has been forwarded to you and you wish to subscribe, click here:

Who we are:

Jörg Luyken: Journalist based in Berlin since 2014. His work has been published by German and English outlets including der Spiegel, die Welt, the Daily Telegraph and the Times. Formerly in the Middle East.

Axel Bard Bringéus: Started his career as a journalist for the leading Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet and has spent the last decade in senior roles at Spotify and as a venture capital investor. In Berlin since 2011.