The end of the banquet | The biggest loser

This newsletter is a four minute read

Dear reader,

Today we ask if a Chinese pork embargo will put the final nail in the coffin of the family farm. We’ll also explain why a loser was pumping his fists after 7 million Germans went to the polls at the weekend.

Regards,

Jörg & Axel

The feast is over

For years now, Germans have been eating ever less of their favourite meat - pork. But at the same time production has been going up. How has this happened?

In one word: China.

That’s right, the booming Chinese middle classes aren’t just buying German cars in abundance, they also can’t get enough of German piggie products. Last year the Chinese imported a whopping €1.2 billion-worth of German pork. (The business is especially lucrative since the Chinese buy titbits like ears and tongues that Germans won’t touch.)

But on Saturday China slammed the door shut. Any pork arriving from Germany as of the weekend will either be burned or marked “return to sender.”

Culpable is a single wild boar that was found dead on the German side of the Polish border last week. Tests on the carcass revealed that the boar had died of African swine fever, a highly infectious and deadly disease in the swine world (rest easy... it is harmless to humans). After spreading for years through eastern Europe, the disease has finally made it over the border.

The Chinese have been trying to eradicate African swine fever from their own stock for years and are particularly careful about whom they import from. Their cautiousness is understandable. The disease can survive for more than 100 days in the processed meat of an infected animal. One confirmed case in your country is all it takes for the Chinese to order an immediate import stop.

For a long time, Germany actually profited from this tough line. As the Chinese burned millions of their own pigs, they had to look abroad to sate that rapidly growing domestic market. Germany stepped into the void. By 2016, every fifth pig killed in Germany was being sent to the Far East.

Now, literally overnight, all that meat has become surplus to requirements. On Friday the price of pork on the German market collapsed as buyers bet on the impending Chinese ban.

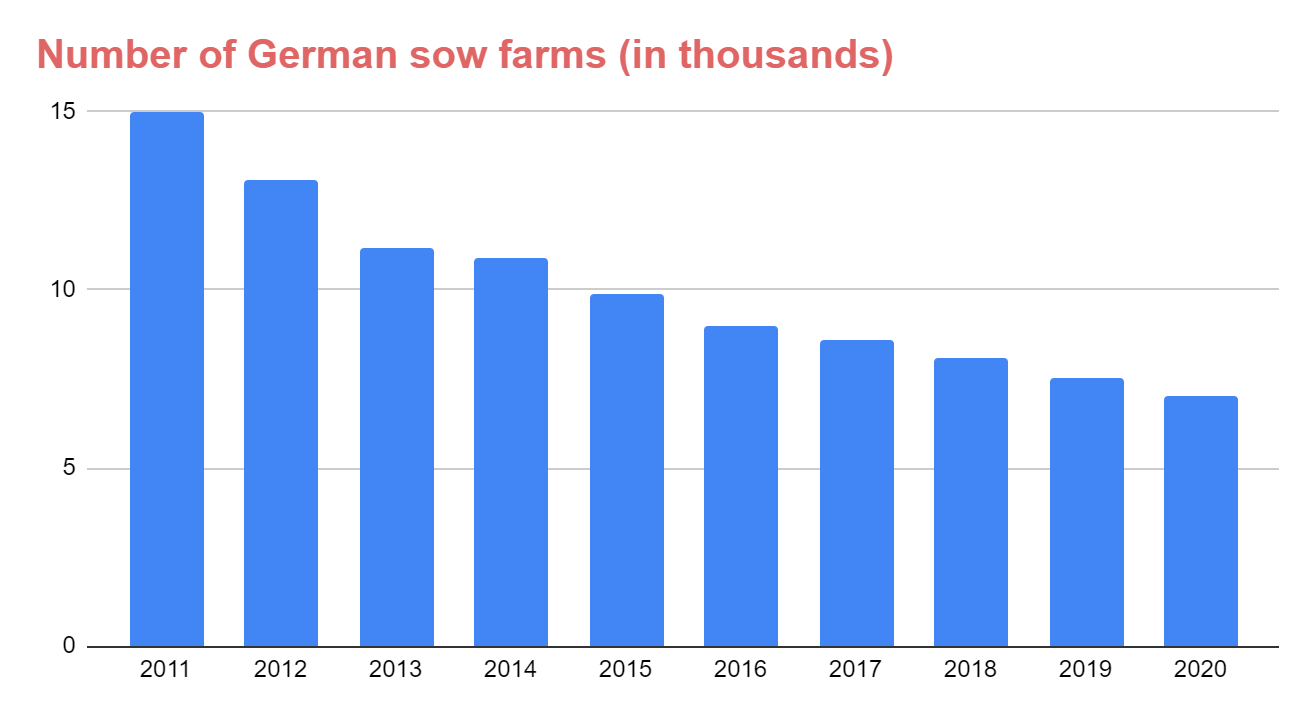

I didn’t know much about the German pork industry when I started researching this article. But one number stuck out to me. While profits were swelling over the past decade, 10,000 small pig farms sold off their land. In a phenomenon known as the Höfesterben, these family-owned farms were gobbled up by companies that rear animals in conditions more like factories than farms.

In the same period, the number of mega farms that hold 5,000 or more hogs has grown by almost 70 percent. These farms are highly specialised, with some solely there to produce piglets and others focused on fattening up hogs.

Small farmers say they can’t afford the investments needed to meet the latest standards set out by the EU on animal welfare. The German agriculture ministry freely admits that the cost of adapting to new regulation means that it only makes sense to build sites that hold 2,000 to 3,000 hogs.

Fed up with Berlin’s agricultural policies, small farmers started driving their tractors into city centres last year to try and raise public awareness. It is these farmers, already living on the brink of bankruptcy, who will be hit hardest by the collapse in the pork price.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Surveys repeatedly show: Germans care about animal welfare, but they also hate industrial farming. Parallel to the death of the family farm, domestic pork consumption has been dropping since 2010, while the market for meat substitutes is booming (although still tiny in comparison). It’s highly ironic that EU standards on animal welfare are leading to the demise of a way of farming that Germans find ethically acceptable.

If the lesson hasn’t yet been learned from Trump’s war on the German car industry, the Chinese pork embargo shows the risk of chasing profits abroad while ignoring domestic consumers. Giving family farms the financial means to meet EU food standards would help save a traditional way of life and encourage Germans to fall back in love with Bratwurst and Schweinehaxen.

J.L.

The biggest loser

Armin Laschet was all smiles at his press conference on Monday. He triumphantly declared that his CDU had won the municipal elections in North Rhine Westphalia (NRW), the state he governs.

Mr Laschet hopes to succeed Angela Merkel as Bundeskanzler next year but first he has to win an internal vote for the party chairmanship. Hence, he has every reason to call the 34 percent the CDU secured in Germany’s most populous state a win.

But winning looks different. Mr Laschet’s party not only lost three percentage points compared to the state’s last municipal election, they have been shedding voters in every consecutive one this century.

What conservative daily F.A.Z. calls a Schönheitsfehler is in fact a trend - the CDU has a leak. Not only in NRW, but everywhere.

CDU support in the dimap Sonntagsfrage 2000-2020:

The drizzle towards the hard right AfD has petered out, voters are now trickling in the direction of the Greens. In NRW the environmentalists came first in Cologne as well as Mr Laschet’s home town of Aachen.

So maybe it wasn’t joy that had Mr Laschet grinning and fistpumping on the podium. Maybe it was Schadenfreude. For the slow drip from the CDU is nothing compared to the torrent of electoral support flowing from the SPD.

This time the Social Democrats were dealt a particularly painful blow. The party has always held onto its heartland, the industrial Ruhr area. In traditionally working class towns like Essen, Dortmund and Gelsenkirchen generation after generation have put their cross next to the SPD, even as coal mines and factories have closed.

Results per electoral district in the Ruhr, NRW municipal elections 2014:

Yet this election was a small revolution - the SPD lost nine of the area’s fifteen electoral districts to the CDU. The Ruhr is no longer red, it’s black.

Results per electoral district in the Ruhr, NRW municipal elections 2020:

The SPD should have ample arguments on their side in next year's election. The Corona epidemic has resurrected the role of the state as guardian of public health and saviour of jobs. Germany’s large number of intensive care units and finely meshed net of Gesundheitsämter have played an important part in keeping the death toll down. And the various billion-euro stimulus measures initiated by the SPD-led finance ministry have kept unemployment at lower levels than expected.

If traditional social democracy doesn't even resonate in the Ruhr - chances are it won’t do so at a national level when Germany goes to the ballots next year.

That might be all that Armin Laschet needs to become Bundeskanzler, should he end up being his party’s choice. But to call him a winner is a stretch. Even as the CDU won the Ruhr they decreased their vote count in twelve out of fifteen districts. The CDU are no winners, they’re just not the biggest losers.

A.B.B.

Who we are:

Jörg Luyken: Journalist based in Berlin since 2014. His work has been published by German and English outlets including der Spiegel, die Welt, the Daily Telegraph and the Times. Formerly in the Middle East.

Axel Bard Bringéus: Started his career as a journalist for the leading Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet and has spent the last decade in senior roles at Spotify and as a venture capital investor. In Berlin since 2011.