Why the SPD have a chance | when Germany ignored a deadly epidemic | shaking up the DAX

Dear reader,

This week we are looking at why the SPD might have a shot at winning next year’s election after all; the epidemic that brought the German health system to breaking point… and was promptly forgotten; and why a Berlin start-up is causing such a stir in Germany’s stuffiest old man’s club - the DAX.

Thank you so much for your helpful feedback - please keep it coming! If you enjoy reading our newsletter, please share it and spread the word!

Btw, next week we will send out two shorter newsletters, plus a weekend roundup - let us know which format you prefer.

Regards,

Jörg & Axel

Big spender Scholz has a shot

In 2014 Wolfgang Schäuble secured his place in history by achieving what his four predecessors as finance minister had all tried but failed to do. He balanced the budget. For the first time in half a century Germany’s tax revenues exceeded its expenses and the state did not need to raise new debt.

Few countries have such a complicated relationship with money as Germany, where budgetary discipline is seen as a moral imperative. Born in 1942, Mr. Schäuble grew up in a post-war society obsessed with financial stability. His CDU party won elections in those days with slogans such as Keine Experimente!

The two sacred cows of Germany’s fiscal policy have been what Schäuble did - balancing budgets and limiting debt. The latter, known as die Schuldenbremse, was even written into the constitution in 2009. Meanwhile the CDU go as far as calling die schwarze Null (“the black zero,” jargon for a balanced budget) their fetish.

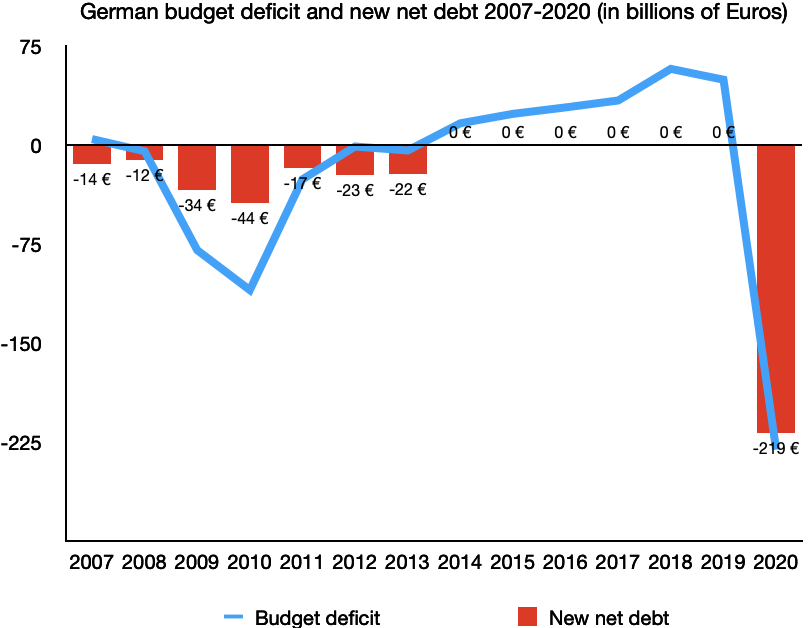

Now, six years after Schäuble’s historic achievement, the Corona-induced economic crisis has compelled his successor, Olaf Scholz of the SPD, to run an unprecedented budget deficit and raise a record amount of new debt.

(Source: Bundesministerium der Finanzen)

Slaughtering this holy cow might seem like an act of sacrilege punishable with banishment. But breaking with fiscal orthodoxy paradoxically presents Mr Scholz’s SPD with a slim shot at winning the 2021 election, something that seemed unimaginable less than a year ago.

Like most Social Democrats, Mr. Scholz is a reluctant convert to the cult of the schwarze Null: he has had to adhere to the CDU line as long as public opinion has demanded it, and has felt it necessary to prove that his party is no worse at managing the economy.

But the public mood is shifting. Even conservative pundits now argue that high debt is manageable as long as debt-financed investments bring in tax revenues which exceed interest rates. They also concede that the debt burden as a percentage of GDP will decrease as long as economic growth is higher than interest rates.

“The schwarze Null should be questioned. As important as the concept might be in good times, Germany now needs to change its fiscal policy.”

said Joachim Lang, CEO of the Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie, already last year.

This change in attitude is fuelled both by rock bottom interest rates and increasing proof that economic austerity (which Germany forced upon its southern neighbours after the financial crisis) might do more harm than good. But there’s also the simple fact that Germany desperately needs to finance investment in schools, roads, high speed internet and other infrastructure to lay the foundations for future growth.

Hence, Scholz can cull the sacred cows with his new favourite weapon - the “bazooka” of a stimulus package he’s already pulled out against the virus.

As the SPD’s candidate for the chancellorship, Mr Scholz surely can’t believe his luck. Hell be the man turning on the taps on public spending in the run up to the election, giving him the credibility to run an election campaign based on what Social Democrats do best - spending money.

A.B.B

The forgotten epidemic

By late March the tide finally seems to be turning. The wave of infections, which has swept over the country since early January, has broken. After weeks in which intensive care units were overflowing, hospitals have some breathing space.

The lack of an effective vaccine, combined with an unusually cold winter, has left the population highly exposed.

At the peak of the epidemic emergency services couldn’t cope with the backlog of call-outs. In central Munich, hospitals stopped taking in patients, leading to a desperate search for beds at suburban clinics. Doctors and nurses in northern Germany were infected en masse, leading to operation rooms being closed.

The final death toll is estimated at around 25,000.

This might sound like a horror scenario for a “second wave” of the corona virus. It is actually what took place during the flu season of 2017/18.

Predicting which strain of influenza will prevail in a particular flu season is something of a lottery. The expectation in 2018 was that a strain of the more deadly Influenza A would dominate. Instead an Influenza B virus of the Yamagata lineage spread through Germany - and the vaccine proved a dud.

Exact numbers are impossible to come by - influenza-related deaths are rarely recorded as such. The Robert Koch Institute, Germany’s public health agency, can only extrapolate the human cost from excess deaths each winter. There is little doubt though: the flu season of 2017/18 was the worst in three decades.

It was unusually dangerous for the young. Of the 1,674 laboratory-confirmed deaths, 10 percent were of people between 35 and 59 years of age, while 20 children under the age of five died.

A lack of comprehensive data on influenza makes comparisons with Covid-19 imprecise. But only one child below the age of 10 has died in Germany after contracting the coronavirus. The average age of the country’s 9,200 Covid-19 deaths is 81 - which corresponds exactly to German life expectancy.

(Weekly deaths in Germany 2016-2020 and COVID-19 deaths 2020. Source RKI and Statistisches Bundesamt)

Looking back at how the Grippewelle (flu wave) of early 2018 was treated by politicians and the media, it is hard not to be struck by the dramatic difference in tone.

In early 2018 Angela Merkel was busy coaxing a reluctant SPD into her fourth government. Towards the end of negotiations SPD leader Martin Schulz caught the flu. Merkel, who had spent more time with Schulz than with her husband over the past few weeks, carried on her job without a second thought.

In Bavaria, the man who would become Mr Lockdown in 2020, Markus Söder, also had a close colleague who'd contracted the virus. His predecessor as state leader, Horst Seehofer, was confined to bed while Söder regaled a packed beer hall at Aschermittwoch with a lengthy monologue on the decadence of Berlin politics.

Just like with the coronavirus, a two-metre distance helps slow the spread of influenza. But there was no social distancing as colleagues congratulated Merkel at her swearing-in ceremony, nor at Söder’s packed booze up.

It wasn’t just politicians. The media also treated the epidemic with a casualness that would shock the sensibilities of a post-corona world.

Der Tagesspiegel allowed itself a little joke at the start of its coverage. “Now even God’s caught it: the singer Karel Gott has been taken to a Prague hospital,” the newspaper joked, before noting that the 78-year-old stood a good chance of dying due to his age.

But the broadsheet told its readers not to worry: “As tragic as every death is, the numbers so far this year are not unusual.”

Were journalists and politicians coldly indifferent to the human cost in 2018? Or are they over-sensitive today? A bit of both probably - the familiarity of the flu jades us to its harm, while the novelty of the coronavirus has turned it into a nightmarish Gespenst. What is indisputable though is that acceptable behaviour has been turned on its head.

Whereas anyone who’d insisted on wearing a mask in public in 2018 would have been met with patronizing smiles from friends and strangers alike, the opposite is true today.

The city of Berlin’s attempt to ban a mass demonstration against the corona restrictions this week was lauded by the political centre. Berlin justified the ban by claiming that the demonstrators would refuse to wear masks. But the decision comes at a time when the strain on the healthcare system is insignificant in comparison with early 2018: currently less than 1 percent of intensive care beds are taken up by coronavirus patients.

The same Tagesspiegel which allowed itself a joke at the expense of a severely ill man in 2018 now damns those seeking a return to normality as Leugner (deniers) - a word charged through its association with Holocaust denial.

According to the German media, the tens of thousands who attended the last demo in early August weren’t stressed parents who’d had to homeschool their children for months, low paid workers worried about their future, or citizens seeking to protect civil liberties. They were conspiracy theorists or far-right scatterbrains.

That some at the last protest were paranoid cranks is without doubt. The campaign to defame them all though - especially coming from an elite who have so quietly changed their moral standards - is woefully lacking in self-reflection.

Still, the courts proved their worth as a check on executive power: in an embarrassment for the Berlin Senate, the demo ban was overturned by the city court on Friday.

J.L.

Heroes, fraudsters and the DAX

Reading the names of the 30 companies making up the DAX, the stock index which measures the performance of Germany’s 30 largest public companies, is like entering an industrial museum. Two thirds of the companies were founded before electric light had gained widespread popularity in the 1880s.

(Source: Wikipedia)

No wonder that newcomer Delivery Hero, an online food delivery platform, is having a tough time during its first week of rubbing shoulders with Volkswagen, Deutsche Telekom and Merck. The company is only nine years old.

Delivery Hero’s entry in the DAX club, as a replacement for Wirecard, which was expelled after the largest accounting fraud in German history led to the company’s implosion, is drawing heavy criticism.

Much of the censure seems wrong headed though. The voices claiming that Delivery Hero is too young and too unprofitable for the DAX simultaneously lament the fact that the Facebooks, Amazons and Apples of the world are all American.

Yet it is those companies' model of sacrificing profits for growth which Delivery Hero is emulating as they invest in delivery personnel, marketing and IT-infrastructure. Even after it entered the S&P 500 index eight years after it was founded, Amazon spent years in the red on its path to becoming one of the most valuable companies in the world.

A quick glance at Delivery Hero’s latest half year report also offers ample proof of the business model’s viability - 70 percent of the company’s losses are the result of large investments in Asia, whereas the Middle East region (which accounts for 30 percent of revenues) is profitable.

Curiously enough, the sceptics are largely the same people who kept faith with Wirecard to the bitter end.

Asset manager DWS lost billions by continuing to invest in Wirecard even as the scandal became public.

DWS board member Christian Strenger’s claim that “with Delivery Hero the Deutsche Börse risks bringing another problem child into the house” leads to questions about German institutional investors' understanding of technology businesses.

None of the hundreds of journalists working for Handelsblatt, Germany’s largest business daily, suspected that the company was a fraud until it was too late.

Instead of joining the chorus of empty criticism of Delivery Hero (and taking swings at CEO Niklas Östberg’s Swedish nationality and preference for t-shirts) Handelsblatt should make sure that it’s them and not the Financial Times which scoops the next German business scandal.

As with any company, Delivery Hero should be scrutinized. It has its flaws, but its admission to the DAX, as a rare German tech champion, is not one of them.

A.B.B

Who we are:

Jörg Luyken: Journalist based in Berlin since 2014. His work has been published by German and English outlets including der Spiegel, die Welt, the Daily Telegraph and the Times. Formerly in the Middle East.

Axel Bard Bringéus: Started his career as a journalist for the leading Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet and has spent the last decade in senior roles at Spotify and as a venture capital investor. In Berlin since 2011.