6 things you haven’t yet heard about Germany's election

Dear Reader,

First of all, sorry about the buzzfeedy headline. I assume you were bombarded with news about the election yesterday, so I stooped this low to grab your attention.

The headline numbers give a big swing to the Social Democrats (SPD), who seemed to be out of the race as little as two months ago but finished a nose ahead of the CDU/CSU with 25.7 percent to 24.1 percent of support.

The far-left Die Linke had such a dismal evening (4.9 percent of the vote) that a left-wing coalition (SPD-Green-Linke) is a mathematical impossibility. Meanwhile, both of the (formerly) big parties have ruled out another “grand coalition” (although they said that last time too).

That leaves two possibilities: the SPD building a three-way coalition with the Greens and the Free Democrats, or the CDU doing the same.

The Greens (14.8 percent) had a poor evening given the high expectations, but still recorded their best ever result. The liberal FDP also scored their best ever result at 11.5 percent. Both now have strong cards in their hands ahead of upcoming Sondierungsgespräche.

Green leader Annalena Baerbock would prefer a coalition with the SPD.

Christian Lindner of the FDP, a friend of Armin Laschet from their time governing North Rhine-Westphalia together, would prefer the conservatives. But he surely knows that the CDU leader is now a dead man walking.

So you knew all that. But did you know this?

1. The ballot slip slip-up

Poor old Armin Laschet, the nice guy from Aachen, has struck a luckless figure all year.

The gaffe that killed him was being caught on camera laughing like an impish schoolboy in the background as President Frank-Walter Steinmeier gave a speech for flood victims in July. That imagine will stay with him forever.

But there were more minor oddities that damaged him.

He wore dress shoes instead of wellies while visiting flood-hit areas; he struggled to mention more than two manifesto pledges when quizzed by one journalist; he reportedly turned up late for stump speeches because he needed regular cigarillo breaks.

More seriously, throughout the winter he swung wildly between favouring lockdowns and advocating for more personal freedom. But he always seemed to have to U-turn when a rise or fall in Covid cases would catch him out.

His final humiliation came on Sunday when he folded his ballot paper the wrong way round, revealing to the waiting press pack who he’d voted for.

It is illegal in Germany to display one’s completed ballot paper. There was some speculation that his vote would be declared invalid, but election authorities in Aachen decided to let him off.

How the CDU boss contrived to fold his ballot the wrong way around is beyond me - it comes ready covered with an extra sheet of paper.

They call Laschet the Rocky Balboa of German politics due to his ability to keep taking punches and still move forward. He hasn’t given up on the Chancellery yet, even as colleagues and journalists alike line up to take a free hit. If he survives this beating someone needs to get Silvester Stallone on the phone.

2. An unexpected CDU triumph

There was an unexpected highlight for the CDU - in a socialist Hochburg.

Die Linke lost just about everywhere you looked. They were even decimated in their former fortresses in the east. Overall they lost around half of their voters.

The biggest humiliation of the evening was losing the constituency of Marzahn-Hellersdorf in east Berlin… …to the CDU.

Marzahn-Hellersdorf is famous for its communist Plattenbau and has been a safe seat for Die Linke ever since reunification. Brush-headed local MdB Petra Pau is almost as unmistakeable as the local architecture.

That the CDU could win in such a red seat would have been unthinkable just a few years ago.

Don’t read too much into it though.

The CDU in the east Berlin district seems to be a one man show. Candidate Mario Czaja was the first ever conservative from the east of town to win a seat in the city senate back in 2006. Recently he has been voluntary head of the capital’s Red Cross and has won plaudits for the management of the city’s vaccine centres.

3. Parties of the future

Income level used to be the dividing line between parties. But perhaps age is becoming the new demarcator.

The liberal Free Democrats were the most popular party among first time voters, while the Greens did best among voters under the age of 25 (with the FDP a close second).

Why do these two parties appeal to the young?

Well, both are socially progressive. They will have no problem finding common ground on fully legalizing abortion, liberalizing drug laws and further supporting LGBT rights.

The fact that both parties are led by people in their early forties no doubt also helps.

But big differences on the role of the state show that young Germans are just as divided as their forebears.

The FDP reject the idea of a state as moral arbiter. They want to hack through bureaucracy and let private entrepreneurs find solutions to problems such as climate change.

The Greens see an interventionist state as necessary in order to create incentives for individuals and companies to change their errant behaviour.

As several commentators have pointed out, Fridays for Future are often used as short hand for the youth vote. It’s a lot more complicated than that.

4. Some things never change

The rise of the Greens and the FDP might suggest that a whole new political landscape is emerging.

But some things remain remarkably consistent over the centuries.

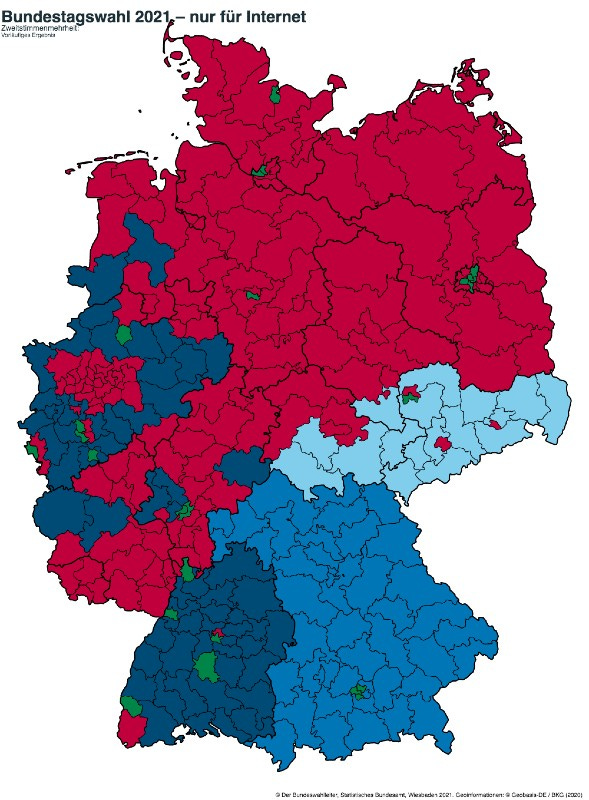

A map showing the most popular party in each district reveals a geographical divide which would have been familiar to Germans living 400 years ago.

The borders between CDU and SPD country roughly follow the dividing lines of the religious wars between Catholic and Protestant states that ended in the treaty of Westphalia in 1648.

As a devout Catholic from the south, Armin Laschet follows in the footsteps of the great CDU leaders, Helmut Kohl and Konrad Adenauer, both members of the Papal religion.

Sober old Scholz, just like every SPD Chancellor before him, grew up in the north as a member of the protestant faith.

The religion of the leader, that is the religion of their subjects. Cuius regio, eius religio.

5. Great night for Sonstige

You might have noticed that Sonstige gained 8.7 percent of the vote, putting “other” in sixth place overall (ahead of Die Linke). It was a big night for the long tail which won its biggest share of the vote since 1949.

What explains this phenomenon?

Partly, it’s continuing a trend. There is a general fragmentation in political loyalty, especially among younger Germans.

Die Partei, a mock-fascist party set up by a group of comedians won half a million votes. A pro-EU outfit called Volt picked up 160,000 list votes.

But there are two reasons specific to 2021 that explain the big numbers for Sonstige.

Firstly a party called dieBasis, set up last summer to protest lockdowns, won an impressive 630,000 of list votes accounting for 1.4 percent of the total.

Secondly, the Freie Wähler, who are junior partner in Markus Söder’s state government in Bavaria, but aren’t well represented outside the southeast, decided to campaign across the country.

Their leader Hubert Aiwanger has become a cause célèbre for anti-vaxxers due to his very public refusal get jabbed against the coronavirus. With more than 1.3 million votes, they doubled their vote share from 2017.

DieBasis and the Freie Wähler both tap into a suspicion of federal overreach and a radical libertarianism that has echoes of the Tea Party in the US.

The former aren’t likely to survive once the last pandemic restrictions have been lifted. But the Freie Wähler are slowly building their strength across the country. We could well hear more from them in the future.

6. Who is the big winner?

Olaf Scholz, of course.

Few people believed him capable of this victory. It is quite the turnaround for a man who suffered humiliation when SPD members picked a pair of no-names to lead the party instead of him back in 2019.

But there is someone else too…

Green co-leader Robert Habeck might be the surprise victor of the evening.

After reaching a back-room deal with Baerbock back in April, he stepped aside to let her take a crack at the Chancellery when polling suggested they could go all the way.

What concession did he get out of her in return though? There is speculation that he will take a more senior role than her in the next cabinet, either as vice-Chancellor or Finance Minister (although the FDP will also want to get their hands on the exchequer).

After Baerbock disappointed as Chancellor candidate, the balance of power inside the environmentalist party has swung back Habeck’s way.

He’ll be the one to watch in the upcoming negotiations.

Remember to sign up for membership in order to support the newsletter and receive my Friday long reads!